Canal Conservation Area

Commentary on emerging issues and opportunities

- Having walked the length of the canals and recorded the existing state as part of the appraisal process, the study recognises each character length has both positive and negative factors that are relevant to the special character and appearance of the conservation area.

- Access to stretches of the canal, particularly in the urban area in Warwick, and for important links in Leamington, needs to be improved so that by increasing use and enjoyment the area becomes safer and more accessible.

- Much of the old town in Leamington is in transition, with areas that were first developed in the 1960s already being redeveloped for residential use. The Althorpe Street area that was cleared of its' traditional workers housing for employment uses as part of the post-war town planning, is part of a proposed Creative Quarter, but also a developers' target for further student housing. The area has the potential to recover and become an active part of the town that again addresses the waterway frontage. A Development framework that extends beyond individual plots would help create a vibrant locality. Particular attention needs to be paid to active frontages, to enhancing the landscape as well as townscape, to ensuring that the waterway is an integral part of what makes up the area, not just a convenient edge.

- The southern extension of Leamington is already underway and the need to promote proper linkages to the existing infrastructure of the canal side was identified but measures to achieve this particularly at the gateway where Europe Way meets the Myton Road, need care and attention. The current roadway is difficult for cyclists and pedestrians particularly. The realignment of the canal to form the roundabout has already changed this from the original rural edge. The further development of residual space under District Council ownership is an opportunity to make this approach more effective, and exploit the inherited asset of the canal. Investment in heritage assets that in some way provide local infrastructure may be eligible for CIL monies.

- In Warwick there are further areas in transition. The profound change to the north side of the canal post-war, particularly between Cape Road Bridge and Coventry Road Bridge did at least maintain landscape margin of open space. Pedestrian links across the canal towards the town centre were something of an afterthought and lack legibility. To optimise the value of the canal corridor as a linking element needs design as part of a movement framework that evolves coherently from better signing initially to fuller integration as change and development takes place. The canal originally served walks and workshops on the town side and could be made to play a part in the redesign that will follow if some further work on how this might be done is carried out.

- There are boundary treatments and some that have arisen from neglect, softened by re-and the colonisation by indigenous vegetation. There are a range of successful frontage treatments that can be employed if this is properly seen as a highway and given that thought and attention. What should not be attempted is to prescribe a standard margin treatment which would replace neglect with monotony.

- The appearance of the canal frontage is blessed by a significant number of mature trees and succession planting needs to be agreed with the canal authority and waterside owners. Conservation area designation is designed to protect trees from wilful damage or inappropriate removal. This needs to be supplemented by a programme of stewardship that recognises how this linear landscape by celebrating the seasons, takes the garden city concept right through the major urban area and out to the countryside the on the towns. Planting alongside the canal a the back of the towpath needs to respond to this as public space, any move to semi private space needs to be sensitive to the transition. There will be cases where private gardens abut the back of the towpath and this is the appropriate place for personalisation.

- The Pocket Park along the restored Saltisford arm could be better linked to the racecourse. Then the Saltisford Common and Warwick Cemetery are part of the Green chain that stretches through to the Coventry Road along the former Warwick and Napton Canal length of the Grand Union. Redevelopment of the County's Montague Road site should at the minimum include a planted corridor but perhaps some moorings space or floating residential. The former wharfs on the offside between Coventry Road and Emscote Road already have some water related activities and these should be retained as part of the visual interest that the corridor can provide whether just for recreation or as part of the walk to work or school.

- Lack of maintenance and poor alterations and replacement windows and rainwater goods are part of the erosion of many historic buildings, equally though redevelopment as a poor pastiche of 'canal side character', threatens the integrity of this as a historic asset by devaluing the true original.

- The NPPF requires that local planning authorities should take into account the desirability of proposals making a positive contribution to local character and distinctiveness. Loss of feature which makes a positive contribution to the significance of the conservation area should be treated as harm, as should proposals outside a conservation area that would affect its setting.

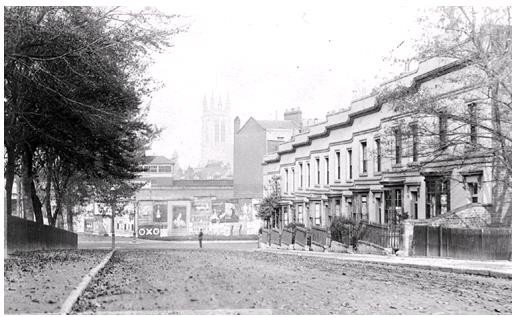

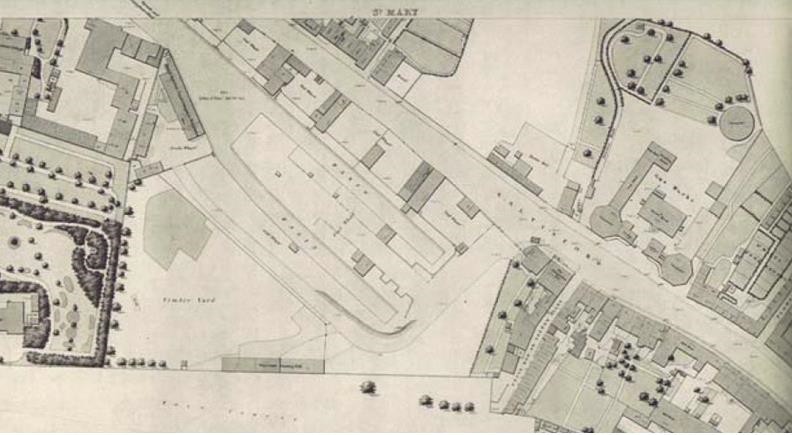

- Further work is needed to record the appearance of what has been lost in the significant amount of changed post war. Fortunately some of the grander schemes such as a new dual carriageway along Tachbrook road which would have resulted in the loss of period buildings never happened. Whereas the clearance of the area between Clement Street and Althorpe Street failed to recognise that some aspects of the character and appearance could have helped avoid the fragmentary redevelopment that did take place. One of the key aims of any conservation study must be to recognise the opportunity to inform change and evolution of what are key elements in what makes the locality meaningful to local people. There are features like the lost wharfs and basins that might be introduced to add a special dynamic to successive redevelopment, such as by St Mary's Road.

- Historic buildings are an important part of the culture of the place, alongside this are the spaces that they frame and the ones that lack shape or identity because there architectural character may not have been preserved well enough. One of the ways in which judgements have been made about character in conservation areas has been to measure how many of the original buildings have suffered changes such as concrete tile roofs plastic windows loss of Street frontage railings. All of these actually can be repaired more sent sympathetically as better higher performance products are developed to respond. So that whilst some of the areas include less well treated buildings, it is wrong to miss the opportunity to set higher standards as they continue to evolve. Where the appraisal has identified historic evidence of the value of a place, it is wrong to just accept a marginal improvement in the aesthetic as being better than what is currently there.

- Local residents and landowners need to have informed advice and guidance to help them preserve and enhance the area. Where redevelopment is proposed then the rationale for how the design develops must be informed by an understanding of how the character and appearance of the canal corridor has evolved and show how the proposals fit into a development framework for future in the change.

- Improving understanding and appreciation this historic asset will help to facilitate dialogue about what is appropriate to change and enhance and is a key element in making the journey along the canal mean more to those that experience it in the future. The successful use of art and temporary events will also bring this to life and help ensure that it continues to be valued and cared for by the communities it serves.

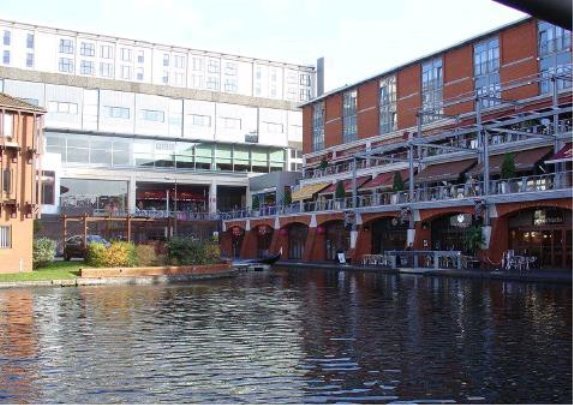

- Part of the interest in the canal is that it is active water space not just somewhere to throw things to make a splash. Support for moorings, waterbased music and art activities, floating galleries and cafes will all help engender a sense of place and a feeling of ownership that is a key element in optimising the value of something built to facilitate the industrial revolution, and to better link Warwick to the world beyond.

- Waterside development increases use of the infrastructure and creates opportunities to positively extend the purposes for which it was made over two hundred years ago. The added value that canals bring should support improvements in public access and the quality of the provision, to sustain increased use by a wide range of users for local walks, cycling, boating, angling and more. The provision of disabled access, potable water, waymarking, mooring bollards, appropriate surfacing, seating, information and interpretation signage, boundary walls and planted boarders, hedge laying and tree planting, marginal waterside vegetation, soft edges suitable for young ducks, are all appropriate ways in which the public benefit of enhancing the Canal Conservation Area can be achieved through development. Screening and security fencing also needs to be of a better quality given the public face the canal presents. As an active highway, WDC expects boundary treatments on both sides of the canal corridor to be sensitive to the local context and avoid restricting use through casual encroachment. Boundary walls above 1metre will require planning consent as will structures proposed to be more than 2.5 metres above the ground within two metres of the boundary.

- The integrity of the waterway as structure is fundamental to the conservation area. Digging foundations , imposing adverse loading on the waterway wall or any act likely to result in a breach of flooding or through discharges to cause pollution or affect the water quality will undermine the designation.

- The NPPF sets out the requirements for an applicant to, as a minimum, describe the significance of any heritage assets affected by a proposal. Individual planning applications are judged on their merits but also have to be considered in the context in which they come forward. Too often they fail to look beyond the red line or accept that if successful they will intensify use of the network beyond their own immediate frontage. Views to and from the waterway can have a direct effect on the character and appearance.

- The Conservation area designation requires judgement about whether a proposal will enhance or damage the quality of the townscape. What contribution does it make to the canalside and broader public realm. Sensitivity to context and the use of traditional materials are not incompatible with contemporary architecture. A particular feature of the linear canal side conservation area is that a site is approached, encountered and then passed, so the three-dimensional quality particularly the experience of ground level including the surfaces and planting employed are experienced sequentially, not as flat elevations . Where doorways are, how windows and other openings are modelled, the details of materials and textures used, the effects of sunlight and shade will all have a bearing on whether it is good enough for the context. This is not one of those areas in which development occurred all in one period and therefore is of a unitary character, but there is a recurring feature which is the waterway including a tow path and sometimes a stock proof hedge. Because the canal side has grown organically over the last two centuries, what might have appeared radical is no longer incongruous, but can enhance, whereas a poor copy erodes the original. If there is an existing structure, then can it be restored and repurposed? Or perhaps remodelled creatively, to get the best of both continuity and change. The former maintenance yard at Hatton is perhaps a good example. A robust existing structure has been given new life. The reuse of heritage buildings safeguards the embodied carbon emitted during the production of the materials used in those assets. Further energy would also be expended during its demolition, disposal of waste materials and in the manufacturing and transport of new materials for the replacement building.

- It is 50 years since the Civic Amenities Act required every local planning authority to look beyond preservation of individual buildings and try to secure quality through identifying which parts of their district are historic assets and thus require a competent design proposal that measures up to that townscape value and to ensure that remains for future generations to enjoy.

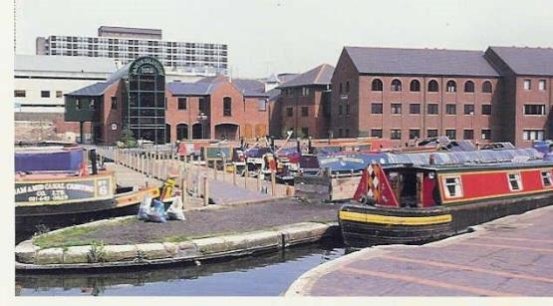

- Conservation and development work together using the historic environment as an asset, and giving it new life is a key factor the economic and social revival of canalside towns and cities such as Birmingham Leeds and Gloucester. The careful integration of heritage assets into regeneration projects over a sustained period such as at Kings Cross, plays an increasingly important and successful role in many major regeneration schemes and transforms the built environment.

- A 'heritage asset' is defined in the National Planning Policy Framework, as "a building, monument, site, place, area or landscape identified as having a degree of significance meriting consideration in planning decisions, because of its heritage interest". Once it falls out of use it is potentially at risk. That is why it is important that the canal corridor continues to evolve and adapt to changing needs, but it is equally important that the special character is not eroded by lack of consideration for what is special.

- Historic England has effectively dispelled the common misconception that listed buildings must be 'preserved' effectively just as they are. This is not the case. Their goal is positive 'conservation' and managing change rather than 'preservation'. The challenge is to work together proactively, using flexibility, vision and innovation to find a solution where 'heritage works' for the owner, occupiers, community and environment at large.

- It is important to celebrate the designation of the CA. Failure by owners to identify the special nature of the canalside corridor lowers the overall environmental quality of the area and can counteract the positive effects of other initiatives taking place. Canalside areas with historic buildings, which individually may not be of particular architectural merit, can still form the basis of effective urban regeneration. People gravitate to historic waterside places, because of their richness they provide a Sense of Place. They are often made up of a variety of spaces, building types, sizes and uses; with interesting architectural features and local character yielding associations with the past. They are of human scale, buildings and townscapes not dominated by cars, promoting social interaction, enhanced well being and quality of life. Regenerating heritage assets can translate into higher values – not just financial value, but economic and social value as well. The wider impacts of regenerating historic assets in terms of their economic and social value may include:

(2) Opportunities for Regeneration

- improvement to the physical fabric of urban areas;

- improvements in personal safety and the reduction of the fear of crime;

- community involvement and sense of ownership;

- employment;

- improvement of image;

- improvement in confidence: a sense of pride;

- indirect inward investment into the wider area; and

- a sustainable use of resources through reuse of past materials and embedded energy.

(1) Managing change

In addition to the condition of the existing fabric, having looked at how the canalsides have changed over the past two centuries, an overall vision of the way in which the settlements will develop and what this will do to the canal corridor over the next 50 years is needed, rather than responding to sites on a piecemeal basis that does not address their part in the character and appearance of the whole historic asset.

Canals impact on built form House building generally remained grounded in local tradition and locally derived building materials until the nineteenth century, when the network of canals and navigable rivers was established for heavy goods. Canal and then railway transport meant that the economic imperative to use only local materials changed and a much wider range of materials became available.

The use of brick at the vernacular level began in the sixteenth century in those parts of the east of England where brick- making had been established during the medieval period. Its gradual spread into other parts of central England to replace, clad or infill external timber-framing was driven at least in part by structural necessity, whereas its use in areas where stone construction was prevalent was initially linked with architectural fashion. By the mid nineteenth century brick was the most widely used building material, its massively increased production driven by improved, mechanised manufacturing techniques and by the more widespread extraction of brick-making clays, often as a companion product of deep coal mining operationsEarly bricks were often uneven in shape and were laid in irregular bonds, but from the seventeenth century when Flemish bond was developed clearly identifiable bonds were adopted so as to allow savings to be made in the number of bricks required and to enhance the neatness of the finish. Increased standardisation and the ending of the Brick Tax (imposed during the wars with Revolutionary France in the 1790s, and abolished in 1850), besides developments in the mass-production of brick and its distribution by rail and canal, made brick the cheapest and most widely available walling material, used for the humblest cottages and hovels which were some of the last manifestations of vernacular building traditions. As both stone quarrying and brick making became more widespread from the late sixteenth century onwards, so ashlar stone and brick, previously restricted in use to higher status houses, were more widely used as building materials for vernacular houses.

In terms of roof coverings, local traditions and materials were far more in evidence before the mid-nineteenth century, when Welsh slate (and to a lesser extent, Cornish slate) was brought to many parts of England by canals and then the railways. Thatch was a universal roofing material and reed, straw and heather were used The size of clay plain roof tiles was standardised in 1477 and their use, favoured for fire resistance, especially in towns, spread outwards from the eastern and south-eastern counties. Up to the arrival of the canals in 1800 roofs were generally covered in hand made clay tiles with some lead and occasionally thatch . After this date, slate began to appear and this accelerated with the coming of the railway mid century, so it soon became the norm , most of the mid to late-19th century houses were roofed with this material. Concrete roof tiles have been used to replace these and better options now exist.

From the mid-nineteenth century relatively uniform streets of terraced houses were built in towns and cities across the land to accommodate the ever-larger workforces demanded by industrial and commercial employers, Prior to that, industrial housing in both urban and rural settings commonly reflected local vernacular traditions, albeit sometimes adapted to provide for the carrying on of industrial or craft processes at home. As living standards rose, pattern books and architectural journals encouraged particular fashions and styles, and as canals and railways made mass-produced building materials more widely available, even the homes of the poor approximated to a national standard and shed a lot off their regional characteristics. Relative numbers of early houses remain very small, which is why there is a presumption to list all pre-1700 examples which retain significant early fabric – significant, that is, in terms of the light it sheds on the development and use of the building.

Where a building forms part of a functional group with one or more listed (or listable) structures this is likely to add to its own interest. Examples include canal,docks and railway purpose-built housing or process buildings associated with industrial or military sites, or agricultural buildings associated with a farmhouse. Key considerations are the relative dates of the structures, and the degree to which they were functionally inter-dependent when in their original uses.Vernacular houses can pose challenges in being adapted for modern living, but listed status does not preclude appropriate adaptation once the special qualities of the building in question are understood and respected.

Georgian windows were predominantly of the sliding sash form, there being few casements, with small panes within elegant, slim glazing bars. In the Victorian period changes in the glass manufacturing process enabled larger sheets to be made and in some buildings the glazing bars were removed and replaced with a single sheet of glass flattening reflections and altering the appearance of a building. Many Victorian and Edwardian houses featured such glass from the start. An unwelcome intrusion in the 21st century has been the arrival of plastic (uPVC) double-glazed windows whose material, construction and detailing are so different from timber they undermine the appearance of a building, especially when they pretend to be what they are not.

The Canal reflects its surroundings. Some buildings have been adversely affected by the replacement of traditional windows with inappropriately designed and detailed new windows and doors and by the use of clumsy modern materials that will degrade and require further replacements. This is an opportunity to provide guidance from Historic England and others as to how this work can be done in a way to restore the character and appearance of the streets and uplift values. Advances in construction technology mean that an exemplary street by street approach to energy conservation and waste treatment in some areas might be an effective way of upgrading the fabric to reduce costs in use and restore some of the original qualities. Conservation management proposals should explore the most effective use of private and public resources.

(1) BUILT FORM RELATED ISSUES

Some poor modern interventions within waterway frontages

Poor quality modern development in some parts

Failure of some modern schemes to respond positively to historic form of development

Creation of large areas in a single use

Pressure for the over-development of some vacant sites

(1) PUBLIC REALM ISSUES

The canal corridor is a special part of the public realm with increasing use and appreciation.

Poor quality pedestrian environment in places, particularly paving and access points

Footpaths and movement framework need some improvement .There is a requirement for a public realm strategy which can then be used to attract Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) finance to fund Implementation of improvements.

Some of the green spaces require management and some improvements with some of the trees in need of tree surgery or replacement in a considered way

Green spaces forming part of the setting of the conservation area should be protected, particularly the open spaces around

Where opportunities arise the town/parish, District and County Councils should work together to seek Improvements to the public realm, access and signage including ways of interpreting the contribution canals make to the quality of the locality.

The appraisal identifies buildings and places which positively contribute to the Conservation Area, either in terms of their character and appearance or their historical interest. Opportunities for enhancement are also identified, along with negative structures these should be acted upon as part of investment in the area.

The Council should as opportunities arise prepare, in consultation with partners, development and planning briefs and masterplans to inform future developments and infrastructure improvement in relation to sites within or in close proximity to the conservation area

There is a policy in the Local Plan (Policy DS17) which commits the Council to undertaking work;

"The Council will prepare and adopt a Canalside Development Plan Document (DPD) to:

- assess the canals in the District and their environment and setting;

- identify areas for regeneration along urban sections, particularly for employment, housing, tourism and cultural uses; and

- identify areas for protection, where these are appropriate, throughout the canal network within the District. This document will designate particular areas and uses and will set out conservation and urban design criteria for use in assessing planning applications."

Issues might include:

Improving access physical and virtual

Increasing use and understanding

Preservation of setting and views;

Building and sites of negative impact

Identifying Potential and exploring Options

Securing trees and hedgerows and green chains;

Intrusion/incursion of domestic garden areas onto canal side;

Quality of canal-side development and finishes;

Living on water, diversity in dwellings

Maintenance and repair of significant buildings;

Loss of original architectural details of some historic assets;

Litter and Rubbish dumping, community adoption

Crime and the perception of crime

Vandalism and neglect, clutter and harm from poor infrastructure

HS2, new roads and other potentially harmful intrusions on character

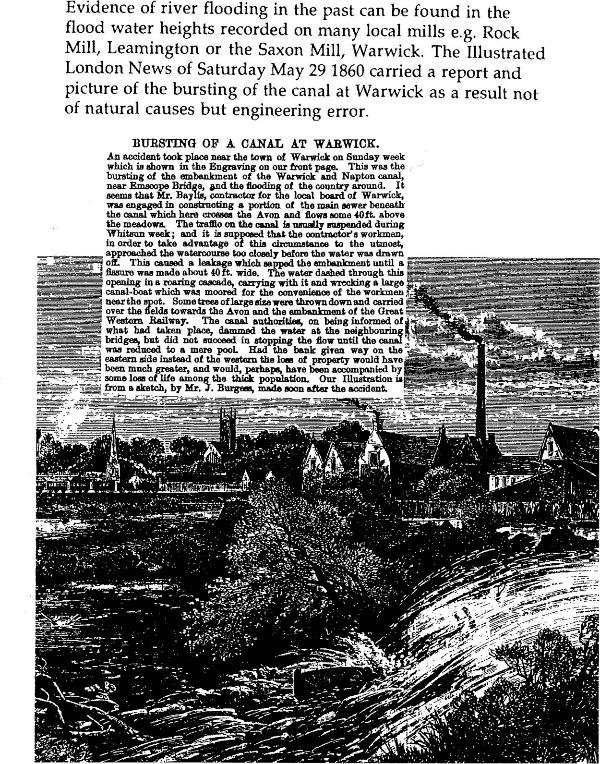

Flooding

Holding water in a canal is a designed process, engineered to ensure that use is beneficial, understanding the history, and how this is done, is a key part to ensuring the integrity of the canal as a historic structure.

The report is a summary of the main findings of a study covering a linear corridor stretching across the district for a length of canals of twenty five miles. This is a broad level of assessment drawing on a range of information from the area and its purpose is to try to develop a common understanding of why this historic asset continues tio have significance when considering proposals for change. It was carried out in late 2017 and 2018 by Roger Beckett RIBA architect/planner for Warwick District Council Conservation .

It is an illustrated narrative, divided into character lengths and describing its historical evolution, highlighting evidence for lost landscapes and buildings, identifying the principal extant buildings and open spaces, their, architectural form and social context, and other elements of the designed landscape around the canals built at the end of the eighteenth and in the first few years of the nineteenth century. The report is an Observation on the present condition and character of the area, the extent to which it retains elements of demonstrable historical significance or amenity value and an indication of any existing designations and the potential to enhance. This is supplemented with guidance to assist with preparing proposals for development.

In the face of significant change within the urban core, the appraisal analyses and defines the special interest and characteristics of the historic structure of the canal and its setting. The appraisal identifies some of the pressures and challenges facing the character of the Canals as a historic asset, to aid the sensitive management, preservation and enhancement of the Canals within Warwick District. The analysis and subsequent recommendations form the evidence basis for the management of change.

The appraisal treats the canals as a coherent linear historic element of special interest that links a series of quite different environments. The appraisal explores them, in order to understand historic associations and current functions, and how the resulting form contributes to the setting of the historic asset. This approach follows conservation principles and enables the different lengths character and appearance, including areas adjacent to be analysed, and the values identified, so as to define the elements that contribute to the special historic and architectural character.

Failure to mention a particular element or detail must not be taken to imply that it is of no importance to the character or appearance of the Conservation Area and thus of no relevance in considering planning applications, as the document can never be completely comprehensive. The appraisal addresses the need to identify, conserve and enhance this aspect of the district's diverse historic environment and manage change in such a way that respects the local character and distinctiveness.

Site visits have taken place at different times of year. Fieldwork was combined with an analysis of historic mapping and other secondary sources are taken into account in assessing the appropriate boundary that recognises a contribution to the character and appearance of the Conservation Area including:, the form and structure of estates and historical settlements; how space is experienced and viewed from within the boundary of the Conservation Area - there are long views from within Conservation Area to the wider landscape that are of significance to the character and appearance; equally the canals and their relationship to the wider landscape can be understood when looking in from outside. The mapping layer will illustrate the setting and contribution of open space (to a depth of approximately two field boundaries). This is not intended to delineate the full extent of the contribution that open space makes to the setting, character and appearance of each character length, but is intended to bring the landscape the canal was designed to pass through into consideration.

Conservation Areas, which are designated by local authorities, have helped to protect the special and unique features of historic places across the country. The purpose of this canal corridor appraisal lies in helping to ensure that change is informed and beneficial use of the waterways as a historic asset is increased.

(1) Places that matter to local communities.

Local planning authorities recognise the need to maintain, or have access to, historic environment records. These are important for informed planning, timely decision-making and increasing public appreciation of their local heritage. National organisations also hold substantial archives and data on heritage and the historic environment. Much of this material suffers from poor accessibility and interconnectivity. One benefit of looking at the canal corridor through the whole district has been the opportunity to bring together local knowledge and historic research.

Further work is needed to identify, digitise and rationalise heritage and historic environment data and records at both national and local levels to make them available for wider professional, academic and public use. This will help to improve the quality and timeliness of planning and decision-making as well as to provide access to original records for family and community history and research. Heritage gives places their character and individuality. It creates a focus for community pride, a sense of shared history, and a sense of belonging.

Local planning authorities play a central role in conserving and enhancing the historic environment. They are best-placed to know how to maximise the benefits of the heritage in their local area and respond to the needs of local communities. They are also well-placed to galvanise partnerships between local government, local communities, private bodies and owners of heritage sites and historic buildings. They rely on specialist advisers to ensure they have valuable expert knowledge of their local areas.

Government advice on the control of Conservation Areas and historic buildings is set out in the National Planning Policy Framework, shortly to be updated. Further advice about Conservation Area control, produced by Historic England as Advice Note 1: Conservation Area Designation, Appraisal and Management, is currently being reviewed along with former English Heritage guidance.

The canals in Warwick District are an integral part of a network managed largely by the Canal & River Trust, as successors to British Waterways

Planning Policy Framework at National and Local level

Conservation is a creative activity to find solutions that conserve historic places and applying cultural values that continue to apply to the future. Legislation recognises the changes that created the canal as a historic place and that managing change is essential to the environment realising its full potential in the future.

Late nineteenth century Campaigns to protect historic sites were seen by many as an assault on fundamental property rights. Since 1882's ancient monuments protection act, legislation has grown to such an extent that what is restricted, and what supported needs clarification. This may be presented by reference to an updateable base so that changes can be factually up to date.

Conservation Areas are created where a local planning authority identifies an area of special architectural or historic interest, which deserves careful management to protect that character. The first conservation areas were designated in 1967 under the Civic Amenities Act, and there are now nearly 10,000 in England.

NPPF and the Canal Environment as a historic place.

Local

planning authorities should set out in their Local Plan a

positive strategy for the conservation and enjoyment of the

historic environment1,

including heritage assets most at risk through

neglect, decay or other threats. In doing so, they should

recognise that heritage assets are an irreplaceable resource

and conserve them in a manner appropriate to their significance. In developing

this strategy, local planning authorities should take into

account:

Local

planning authorities should set out in their Local Plan a

positive strategy for the conservation and enjoyment of the

historic environment1,

including heritage assets most at risk through

neglect, decay or other threats. In doing so, they should

recognise that heritage assets are an irreplaceable resource

and conserve them in a manner appropriate to their significance. In developing

this strategy, local planning authorities should take into

account:

- the desirability of sustaining and enhancing the significance of heritage assets and putting them to viable uses consistent with their conservation

- the wider social, cultural, economic and environmental benefits that conservation of the historic environment canbring

- the desirability of new development making a positive contribution to local character and distinctiveness; and

- opportunities to draw on the contribution made by the historic environment to the character of a place

NPPF PARAGRAPH 126.

National Planning Policy

Conservation Areas are designated under the provisions of Section 69 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. A Conservation Area is defined as, 'an area of special architectural interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance'. Section 71 of the same Act requires Local Planning Authorities to formulate and publish proposals for the preservation and enhancement of any parts of their area which are Conservation Areas. Section 72 specifies that, in making a decision on an application for development in a Conservation Area, special attention shall be paid to the desirability of preserving or enhancing the character or appearance of that area.

This Conservation Area Appraisal should be read in conjunction with the principles and policies set out in Section 12 of the National Planning Policy Framework; Conserving and Enhancing the Historic Environment. Guidance by Historic England and Conservation Principles EH2008

Significance and Setting

As the National Planning Policy Framework makes clear, significance derives not only from a heritage asset's physical presence, but also from its setting.

Heritage assets may be affected by direct physical change or by change in their setting. Being able to properly assess the nature, extent and importance of the significance of a heritage asset, and the contribution of its setting, is very important to understanding the potential impact and acceptability of development proposals.

In most cases the assessment of the significance of the heritage asset by the local planning authority is likely to need expert advice in addition to the information provided by the historic environment record, similar sources of information and inspection of the asset itself. Informed analysis is required as harm may arise from works to the asset or as is particularly relevant to a linear heritage asset, from development within its setting.

Constructive conservation is concerned with the positive contribution that conservation of the setting of heritage assets can make to sustainable communities and for the desirability of new development making a positive contribution to local character and distinctiveness.

Substantial harm.

What matters in assessing if a proposal causes substantial harm, is the impact on the significance of the heritage asset.

Whether a proposal causes substantial harm will be a judgment for the decision taker, based on; having credible, reliable information on the proposal; having regard to the circumstances of the case; and on the policy in the National Planning Policy Framework. Substantial harm is a high test, one important consideration might be whether the adverse impact seriously affects a key element of its special architectural or historic interest. While the impact of total destruction is obvious, partial destruction or alteration can have a considerable impact but, may still be less than substantial harm. It may not be harmful at all, for example, when removing later inappropriate additions to historic buildings which harm their significance.

Similarly, works that are moderate or minor in scale are likely to cause less than substantial harm or no harm at all.

However, even minor works have the potential to cause substantial harm. Policy on substantial harm to designated heritage assets as set out in the National Planning Policy Framework is:

When considering the impact of a proposed development on the significance of a designated heritage asset, great weight should be given to the asset's conservation. The more important the asset, the greater the weight should be.

Significance can be harmed or lost through alteration or destruction of the heritage asset or development within its setting. As heritage assets are irreplaceable, any harm or loss should require clear and convincing justification.

Substantial harm to or loss of a grade II listed building, park or garden should be exceptional. Substantial harm to or loss of designated heritage assets of the highest significance, notably scheduled monuments, protected wreck sites, battlefields, grade I and II* listed buildings, grade I and II* registered parks and gardens, and World Heritage Sites, should be wholly exceptional.

NPPF PARA 132

Where a proposed development will lead to substantial harm to or total loss of significance of a designated heritage asset, local planning authorities should refuse consent, unless it can be demonstrated that the substantial harm or loss is necessary to achieve substantial public benefits that outweigh that harm or loss, or all of the following apply:

- the nature of the heritage asset prevents all reasonable uses of the site;and

- no viable use of the heritage asset itself can be found in the medium term through appropriate marketing that will enable its conservation;and

- conservation by grant-funding or some form of charitable or public ownership is demonstrably not possible;and

- the harm or loss is outweighed by the benefit of bringing the site back intouse.

NPPF PARA 133

In determining planning applications, local planning authorities should take account of:

- the desirability of sustaining and enhancing the significance of heritage assets and putting them to viable uses consistent with their conservation

- the positive contribution that conservation of heritage assets can make to sustainable communities including their economicvitality

- the desirability of new development making a positive contribution to local character and distinctiveness

NPPF PARA 131

Local planning authorities should not permit loss of the whole or part of a heritage asset without taking all reasonable steps to ensure the new development will proceed after the loss has occurred.

NPPF PARA 136

Local planning authorities should look for opportunities for new development within Conservation Areas and World Heritage Sites and within the setting of heritage assets to enhance or better reveal their significance.

Proposals that preserve those elements of the setting that make a positive contribution to or better reveal the significance of the asset should be treated favourably.

NPPF PARA 137

Local planning authorities are to formulate and publish proposals for further preservation and enhancement of their Conservation Areas. The Appraisal may not make mention of every building or feature within the conservation area but any omission should not be taken to imply that it is not of any interest or value to the character of the area.

This conservation area appraisal will be used to inform decisions on planning, listed buildings and conservation area applications.

Local Planning Policy of particular relevance to the canal.

DS1 Supporting Prosperity

The Council will provide for the growth of the local and sub-regional economy by ensuring sufficient and appropriate employment land is available within the district to meet the existing and future needs of businesses

DS2 Providing the Homes the District Needs

The Council will provide in full for the Objectively Assessed Housing Need of the district and for unmet housing need arising from outside the district where this has been agreed. It will ensure new housing delivers the quality and mix of homes required, including: a. affordable homes; b. a mix of homes to meet identified needs including homes that are suitable for elderly and vulnerable people; and c. sites for gypsies and travellers

DS3 Supporting Sustainable Communities

The Council will promote high quality new development including: a) delivering high quality layout and design that relates to existing landscape or urban form and, where appropriate, is based on the principles of garden towns, villages and suburbs; b) caring for the built, cultural and natural heritage; c) regenerating areas in need of improvement; d) protecting areas of significance including high-quality landscapes, heritage assets and ecological assets; e) delivering a low carbon economy and lifestyles and environmental sustainability.

The Council will expect development that enables new communities to develop and sustain themselves. As part of this, development will provide for the infrastructure needed to support communities and businesses, including:

a) physical infrastructure (such as transport and utilities); b) social infrastructure (such as education, sports facilities and health); c) green infrastructure (such as parks, open space and playing pitches).

DS17 Supporting Canalside Regeneration and Enhancement

The Council will prepare and adopt a Canalside Development Plan Document (DPD) to: i. assess the canals in the district and their environment and setting; ii. identify areas for regeneration along urban sections, particularly for employment, housing, tourism and culturaluses; and iii. identify areas for protection, where these are appropriate, throughout the canal network within the district.

This document will designate particular areas and uses and will set out policies for use in assessing planning applications

The Council wishes to see the canals reach their full potential, providing not only for leisure pursuits but also for the possibility of opening up and regenerating areas that have fallen into disuse over time, particularly where this may help to boost the local economy by providing new jobs. A holistic approach is needed to avoid piecemeal development that may result in the sterilisation of other sections of the canalside. By carrying out a study into what activity is currently taking place along the canal and within its environs, the Council can plan for a sustainable and productive future. A Development Plan Document produced by the Council will be able to allocate specific sites for appropriate uses whilst building on and reinforcing existing successful canalside developments. This should result in a set of proposals to guide sustainable and dynamic future development that contributes to the prosperity of the district.

It is intended that this Development Plan Document will also bring forward three of the employment areas (Sydenham Industrial Estate, Cape Road / Millers Road, Montague Road) identified for redevelopment for residential uses (see Policy DS8). It is important that proposals for these areas are developed to take account of their canalside location and brought forward as part of the wider uses outlined in this policy.

13.5 hectares of employment land is being provided as replacement to allow for the redevelopment of poor quality employment land. The Council has undertaken a review of industrial estates within the district and identified the following areas as being less capable of providing the right type of employment land in the right location to meet future business needs:

- Sydenham Industrial Estate, Royal Leamington Spa

- Cape Road / Millers Road, Warwick

- Montague Road Industrial Estate, Warwick

- Common Lane, Kenilworth

These industrial estates arose to accommodate small-scale local manufacturing and are characterised by building stock that no longer reflects the requirements of many businesses. Decline in manufacturing and the fact that modern manufacturing processes need smaller footprint buildings means levels of vacancy on these sites will increase. In addition these industrial estates do not have easy access to the strategic road network and, being located within or adjacent to residential areas, do not offer the most suitable environment for certain employment uses. Three of these areas are located adjacent to the canal and therefore will be brought forward through the Canalside DPD (see policy DS17).

local plan Para 2.28

HS1 Healthy, Safe and Inclusive Communities

The potential for creating healthy, safe and inclusive communities will be taken into account when considering all development proposals. Support will be given to proposals that:

a) provide homes and developments that are designed to meet the needs of older people and those with disabilities; b) provide energy efficient housing to help reduce fuel poverty; c) design and layout development to minimise the potential for crime and anti-social behaviour and improve community safety; d) contribute to the development of a high-quality, safe and convenient walking and cycling network; e) contribute to a high-quality, attractive and safe public realm to encourage social interaction and facilitate movement on foot and by bicycle; f) seek to encourage healthy lifestyles by providing opportunities for formal and informal physical activity, exercise, recreation and play and, where possible, healthy diets; g) improve the quality and quantity of green infrastructure networks and protect and enhance physical access, including public rights of way to open space and green infrastructure;

HS2 Protecting Open Space, Sport and Recreation Facilities

HS4 Improvements to Open Space, Sport and Recreation Facilities

Contributions from developments will be sought to provide, improve and maintain appropriate open space, sport and recreational facilities to meet local and

district-wide needs. The public rights of way network within the district is a valuable resource for local people in its ability to support healthy and active lifestyles and reduce reliance on private vehicles. Development proposals, whether in urban or rural settings, should seek to enhance connectivity to these networks, in particular where there is already limited access. Wherever possible, good connectivity to the existing public rights of way network will be required.

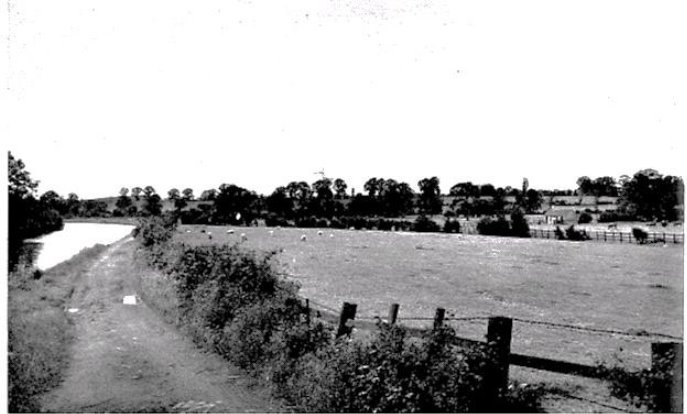

LAPWORTH LOCK7 STRATFORD CANAL 1971 NWM

HE2 Conservation Areas

There will be a presumption in favour of the retention of unlisted buildings that make a positive contribution to the character and appearance of a Conservation Area. Consent for total demolition of unlisted buildings will only be granted where the detailed design of the replacement can demonstrate that it will preserve or enhance the character or appearance of the conservation area.

Measures will be taken to restore or bring back into use areas that presently make a negative contribution to conservation areas. It is important that development both within and outside a conservation area, including to unlisted buildings, should not adversely affect its setting by impacting on important views and groups of buildings within and beyond the boundary.

NE1 Green Infrastructure

The Council will protect, enhance and restore the district's green infrastructure assets and strive for a healthy integrated network for the benefit of nature, people and the economy.

NE2 Protecting Designated Biodiversity and Geodiversity Assets .

The Council will protect designated areas and species of national and local importance for biodiversity and geodiversity

NE3 Biodiversity

New development will be permitted provided that it protects, enhances and / or restores habitat biodiversity.

NE4 Landscape

New development will be permitted that positively contributes to landscape character. Development proposals will be required to demonstrate that they: a) integrate landscape planning into the design of development at an early stage; b) consider its landscape context, including the local distinctiveness of the different natural and historic landscapes and character, including tranquillity; c) relate well to local topography and built form and enhance key landscape features, ensuring their long term management and maintenance; d) identify likely visual impacts on the local landscape and townscape and its immediate setting and undertakes appropriate landscaping to reduce these impacts; e) aim to either conserve, enhance or restore important landscape features in accordance with the latest local and national guidance; f) avoid detrimental effects on features which make a significant contribution to the character, history and setting of an asset, settlement, or area; g) address the importance of habitat biodiversity features, including aged and veteran trees, woodland and hedges and their contribution to landscape character, where possible enhancing these features through means such as buffering and reconnecting fragmented areas.

NE7 Use of Waterways

The waterways can be used as tools in place making and place shaping, and contribute to the creation of sustainable communities. Therefore, any development should not:

a) adversely affect the integrity of the waterway structure; b) adversely affect the quality of the water; c) result in pollution due to unauthorised discharges and run off or encroachment; d) adversely affect the landscape, heritage, ecological quality and character of thewaterways; e) adversely affect the waterways potential for being fully unlocked or discourage the use of the waterway network

Whilst regeneration and reuse is to be supported, there are clear reasons for managing the type and nature of new development in order to protect the environment. These include the presence of many listed buildings and their settings and the natural environment and biodiversity, some of which has evolved as a direct result of the former neglect of the waterways. The historic environment includes buildings and structures pertaining to the previous uses of the canal network as a major carrier of goods and includes wharfs, towpaths, bridges and buildings that may be listed nationally or included on local lists or of interest because of their historic industrial importance to the localarea.

Culture, Leisure and Tourism

The district has many historic assets that operate as visitor attractions, such as castles in Warwick and Kenilworth, Stoneleigh Abbey, the country houses of Packwood and Baddesley Clinton and the canal network, as well as the regency buildings and parks of Royal Leamington Spa. The district also has other attractions such as Hatton Country World and Stoneleigh Park, all of which generate approximately 3.9m trips a year to the area.

The estimated spend is £257m and supports over 4,180 jobs. The close proximity of Stratford-upon-Avon provides a strong cross-border tourism offer . The Council's strategy sees tourism as being a key part of the local economy and this Plan should promote and deliver tourism in a proactive and positive way.

The district's cultural assets and visitor facilities should be supported to grow and improve in ways that maintain their attractiveness and integrity; this will be the case particularly for those assets associated with the historic environment. It is an objective of this Plan to enable the maintenance and improvement of leisure facilities, including supporting appropriate opportunities for culture and tourism.

Managing change

Warwick District Council Local Plan has identified that Waterways can be used as tools for place making and place shaping and contribute to the creation of sustainable communities (Warwick District Local Plan NE7). The Council wishes to see the canals reach their full potential, providing not only for leisure pursuits but also for the possibility of opening up and regenerating areas that have fallen into disuse over time, particularly where this may help to boost the local economy by providing new jobs. A holistic approach is needed to avoid piecemeal development that may result in the sterilisation of other sections of the canalside. The local waterways link historic towns with the countryside beyond. An ecological resource, they provide open access to a landscape of character for the many residents who do not have their own garden, want to walk, jog or cycle along the 40 Km of Canal in Warwick District. By realising the potential of this heritage asset, increasing safe use and enjoyment.

The Canal Conservation Area seeks to promote intelligent and inspired design, which is responsive to local distinctiveness and respects history and context, that can bring about economic and social benefit

Attracting people to live, work and play in the locality will increase the return on the legacy of local investment that created this enduring national heritage asset.

'Local planning authorities should look for opportunities for new development within Conservation Areas and World Heritage Sites and within the setting of heritage assets to enhance or better reveal their significance.

Proposals that preserve those elements of the setting that make a positive contribution to or better reveal the significance of the asset should be treated favourably.'- NPPF Paragraph 137.

Canals works were sometimes spectacular achievements, given the spade and barrow technology, the infancy of contracting, the ingenuity and industry required of both engineers and of promoters in gaining the rights, to carry out the work. Whatever the effort to create, and the impact of gangs of navvies on the unsuspecting countryside, apart from the occasional breach, they moved gently through the countryside and emerging towns. They opened up trade in what was in the eighteenth century still an agrarian society. They facilitated the growth of settlements and manufacturing by allowing materials won in one place to be worked in another, with the products distributed around the country. They provided inland economies such as Warwickshire with an alternative to the horse packed with baskets or trailing a carriage over uneven ground. For this reason they are often overlooked, benign stretches or just a bump in the road, like at Emscote. Their creation over two hundred years ago was a speculation that makes crowd funding quite unexceptional. In many ways they showed how innovation, enterprise and collaboration could be profitable and development beneficial in the short term, but that also provided a legacy that continues to be put to use. For canals to continue to have a welcome place in the local environment, they need to respond positively to opportunities without destroying what is valued and of significance. The canal was deliberately aligned to optimise its potential as infrastructure, and facilitated the development of land in the ownership of some of the canal act's promoters like Greatheed, Willes and Wise. Some of the original uses ,such as wharfage, have virtually disappeared ,and the land has been repurposed to meet subsequent needs, without losing the association with its past.

The two principal towns, differ in their characteristics. Warwick had evolved over nine hundred years before the canal arrived at the end of the eighteenth century. It was a town of 6000 people whereas Leamington had 315 - the population grew 40 times in the 40 years to 1840. The existing conservation areas differ too.

Warwick 's is predominantly landscape with the Racecourse, Priory and St Nicholas Park and the Castle Park and grounds . The latter, which is largely unfamiliar to local people, It is of course a registered park ,created for the earl in the mid eighteenth century by 'Capability' Brown. The waterside open space in Leamington, 'Spa garden's is also registered, but the conservation area is mainly populated by buildings and overlaps with the canal character area.

The spa drew water from a fissure in the Bromsgrove sandstone rock bed, this is known locally as Warwick stone, a stone used on some of Warwick's diverse building stock. Sandstone from Rock Mills at Emscote was boated down for William Eborall's masons to construct Robert Milnes design for the elegant new bridge for the Earl of Warwick in 1793. The stone was also used to construct the three arches that carry the canal over the Avon completed in 1799 by Charles Handley, with assistance from Henry Couchman. South of the River Leam,the canal in Leamington is on the clay rich Mercia Mudstone. Leamington's regency style is stucco on brick to echo the stone buildings in Georgian Bath. Exceptions include the large round columns to the front of the pump room in a sandstone brought by water from Derby, as would have been the slate for roofs,

The Canal Conservation Area should ensure that development reinforces the distinctive character of the canal in its different lengths, some urban, some rural, and recognises the diverse role it plays in the culture and economy of the district. Created to overcome some of the topographical hurdles Warwickshire faced being limited in navigable rivers and far from the sea, the canals assumed a significance moving coal, building materials and the products of the industrial revolution it helped facilitate.

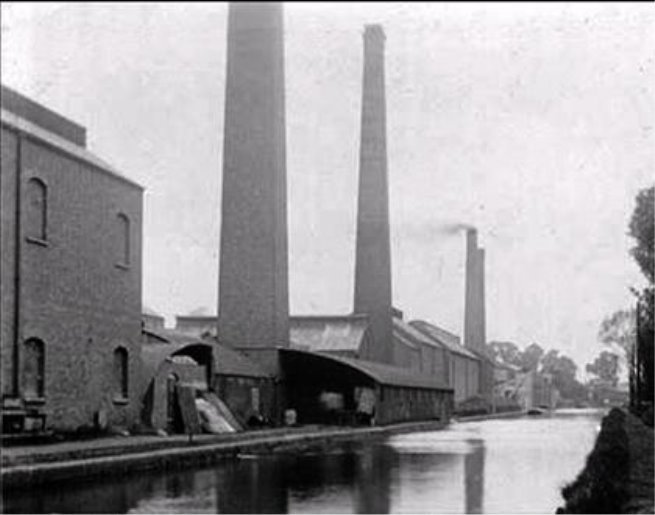

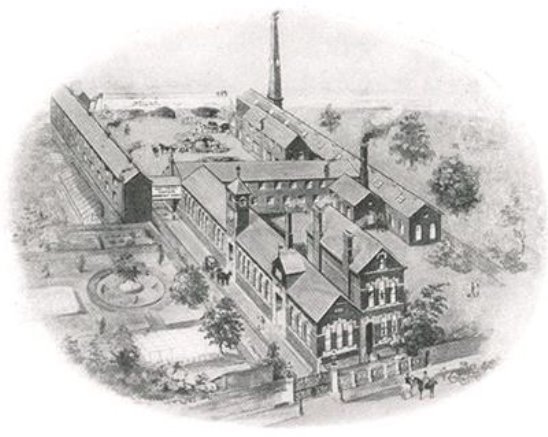

NELSON WORKS WHARF STREET WARWICK WCRO

Over 2000 miles of canals and navigable rivers extend across the country. About 500 miles of canal has been designated as Conservation Areas, sometimes as a convenient boundary. Generally the character of a Canal Conservation Area extends beyond the waterway authority's ownership as a visual envelope in which a loss of enclosure, from the removal of trees or a waterside building, can have a significant effect, equally so can development. This should be designed to make a positive contribution.

Canals in Warwick District pass through countryside, villages, urban fringe and towns, bringing wildlife into urban areas, towpath verges and linking open spaces. Species include water voles and otters, fish and bats, that all make use of this connected linear route. Habitat conservation and creation must be considered alongside navigation, recreation and built heritage character and appearance. The impact on waterside edges and the waterbody itself are also part of the balance. From encouraging the use of native plant species in landscape design and management, to more detailed biodiversity plans, or the control of pollution, these are all matters that determine the local authorities response to proposals.

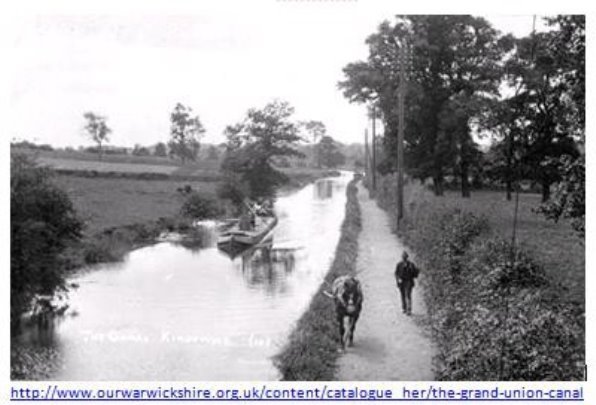

CANAL AT KINGSWOOD

The council believes the waterside is an asset that should be available and accessible to all local residents and visitors to the district. Although priority will be given to pedestrians so that they may benefit from the many opportunities that walking can give, the council wishes to encourage cycling, and the waterside can also provide part of a traffic-free route for cyclists.

To enhance use there is a need to;

- Continue to improve the environment of the canal , the quality of the towpath and the surrounding footpath network as well as new buildings of quality

- Make more of its significant attractions – Hatton flight, Avon Aqueduct, and the listed lengths of the Stratford Canal

- Make more of its history and industrial archaeology through interpretation, together with public art, wayfinding.

- Provide gateways to the canal linked to neighbourhood routes, parking and public transport. The main public transport asset is the railway as the Chiltern line follows the Grand Union canal to Birmingham with stations at Leamington , Warwick, Warwick Parkway, Hatton, and Lapworth, where the Stratford Canal stretches south and northward to the district's boundaries at Hockley Heath and Yarningdaqle Common..

- Improve links with the surrounding communities for visitor infrastructure such as pubs, cafes, toilets and visitor information and interpretation, with access to the canal by road and public transport as well as cycling and walking routes.

- Identify development opportunities along the canal that will improve the environment and increase activity. Development should improve access from surrounding residential areas to the canal.

- Increase use of the water for boating and leisure activities including moorings and where possible new basins

- develop more the usage by local people and expand the draw of the canal to bring in visitors.

- A key observation is that the canal itself provides a traffic free route between the towns and villages and potential walk to work routes. The unimproved sections of towpath are sometimes too narrow for cyclists and walkers too pass and there are hazards at the bridges, whereas parts make an excellent cycle route and link to the national cycle network. There are potential conflicts with anglers and the points of access are poor for mobility scooters.

WDC's Health and well being agenda aims to open up the canalside for greater public access, this includes through-site links in new waterside development, and access to the towpath as a generally accessible and safe walkway along the whole length of the canals through the district and beyond. New footpath links will normally be pursued when redevelopment of waterside land takes place. In instances where development or intensification creates a direct need to improve or enhance an existing section of the waterside, planning conditions may be imposed or developer contributions sought.

The Council will encourage the development of the recreational and leisure potential of the canal in so far as this does not adversely affect the nature conservation interest and is consistent with the capacity of the waterway and the amenity of the surrounding area. The Council will seek to ensure that existing water-based activities are not displaced by redevelopment or change of use.

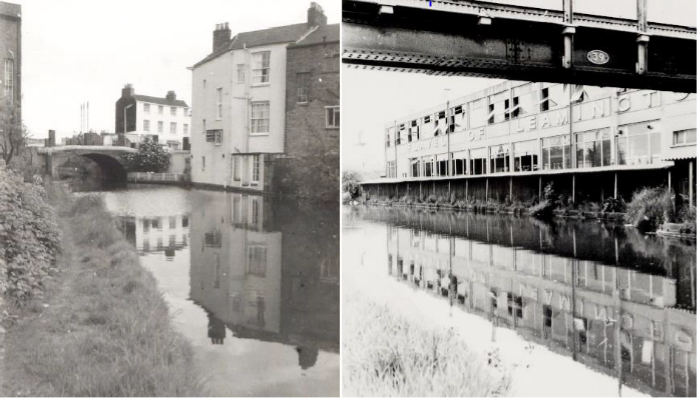

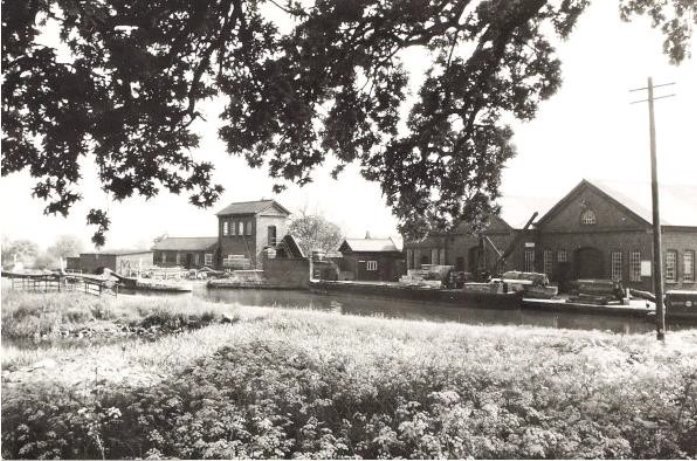

CLEMENS ST BRIDGE AND FLAVELS WATERSIDE AT LADDER BRIDGE WATERWAYS COLLECTION WRCO

In addition to the general design policies, development on the canalside needs to respect the unique character of the waterways, so that it is of a high quality of design that is informed by its context, having particular regard to the massing of development and its relationship to the canal corridor conservation area status. The canal has a nature conservation value and development must protect its ecological value and not harm biodiversity. The aim is to secure a special quality for all new development and where appropriate to enhance the vitality of the canals and include related uses that attract the public.

There is a need to consider the design of individual buildings as well as the spaces around them and broader urban design issues. This must be done with a full understanding of the context, local character and heritage assets of the area. Historical value derives from the ways in which past people, events and aspects of life can be connected through a place to the present. It can be illustrative or associative. The aesthetic meanings are a sensory and intellectual response to the design intentions. Characterisation of the historic canal environment is designed to identify quality and what is valued so that it contributes to a shared vision of what contributes to a sense of place.

Understanding the value of historic canal corridors informs good practice. Applicants need to provide sufficient information for the local authority to determine an application, and reveal how the existing character of the canal conservation area has been considered in proposals. This should minimise adverse impacts, but also recognise the opportunities to increase the beneficial use of waterways to continue to shape the place and enrich the local environment.

the council will require the submission of a design statement as part of a planning application. The statements should typically address scale, mass, height, density, layout, and quality of materials, in relation to the local context, historic structures and archaeological remains; the impacts on navigation and ecological interests; visual and physical permeability and protecting and enhancing public access to and along the waterside, landscaping, open spaces and street furniture and any proposals that involve lighting.

The council will refer to the Canal Conservation Area Appraisal to assist in identifying the qualities of the Area, including:

- the character of individual lengths within the district;

- structures, landmarks, landscapes and views of sensitivity and importance;

- negative and gap sites eroding special character, development sites and regeneration opportunities;

- the contribution that the landscape makes to the setting of the 18th century asset;

- sites of archaeological importance;

- focal points (existing and proposed) of public activity; and

- public access and recreation opportunities.

We will consult CRT, IWA and other stakeholders as appropriate on developments affecting the canals. A balance must always be struck with regard to other issues such as ecological and navigational interests and the amenity of residential neighbours. The redevelopment of canal wharves or basins for other land uses should consider whether any restoration potential exists.

When proposals alongside the canal come forward, the council's emphasis will often be on promoting a mix of uses, including active businesses serving pedestrians and cyclists, whilst also maintaining this waterway corridor as an important route. The council will expect water related uses on the canal where appropriate and will expect development proposals that do not include such uses to provide evidence as to why this is not the case. All proposals will be expected to provide improved accessibility and connectivity to the surrounding areas, enhancement of the canalside towpath, protection of views, minimising the impact on biodiversity and wildlife habitats and promotion of the canal and towpath as a health, sport and recreation resource. The design of new development along the Grand Union canal will need to take into account the Canal conservation area and its evolving character.

New development considerations in conservation areas, aside from NPPF requirements such as social and economic activity and sustainability, are appropriate proportion, height, massing, use of materials, durability and adaptability, use, enclosure, relationship with adjacent assets and definition of spaces and walks, alignment, active frontages, permeability and treatment of setting.

WDC's Listed buildings and conservation area guidance 2010 provides advice on the expectations that affects a historic asset or its setting.

There is a presumption that buildings which make a positive contribution to a CA should be retained, preferably in a continuation of their original use. This may require updating of the services in the building or adaptations to improve access. Changes that harm the significance or diminish its' contribution are not appropriate. The incremental development of a diverse canalside should mean that compatible new buildings will allow the area to continue to evolve and can add to locally distinct character. This is to be preferred to bogus copies or poor pastiche which will undermine the original.

Detrimental changes that harm an area can arise through change in use or intensification as well as by neglect. The council has powers to remedy structures in a conservation area even those that are not listed. Changes that harm the character can be affected by siting as well as the scale form and materials of a building as well by the introduction or loss of landscape elements including surfacing, boundaries and planting. The intrusion of vehicles on the canalside is often a harmful change to what is generally experienced best on foot.

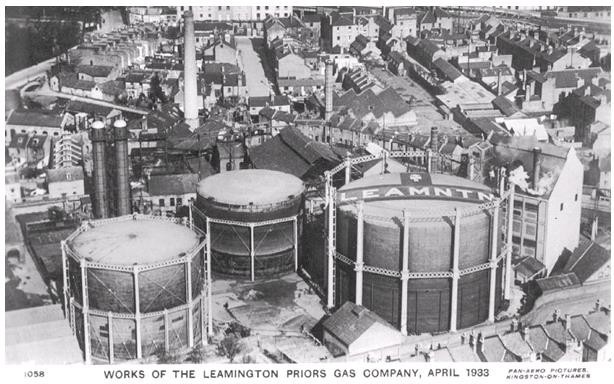

WOODLOES FIELD S WARWICK 1946 ABERCROMBIE REPORT

The enclosure or openness of particular sections of the canal should be respected as this quality contributes significantly to its varying character.The ever changing views, the variety and contrast of townscape elements and the informal relationship between buildings and canal make significant contributions to the character of the canal. Different sections of the canal vary considerably in terms of aspect, level, width and orientation and in the nature and function of adjacent buildings and landscape.

The appraisal has not marked specific views. The canal is experienced as a continuous linear element, so that the evolving view as one travels along is a key characteristic. The preservation of the essential qualities of any view, or indeed the enhancement of those qualities will be sought. The impact of any proposal on these views will therefore form part of any evaluation of a proposal affecting heritage assets and other areas of townscape sensitivity.

Although the canal is a continuous open space, it is not always perceived as such because of its twisting route. The canal has a picturesque quality with only stretches being visible at any one time and views partly curtailed by the bends in the canal and the bridges which cross it and frame distant views. The canal side trees hedgerows and informal plant margins, often along very narrow strips, give a soft edge to the water way and contrasts with the harder edge formed by some of the enclosing structures. There is strong support for the picturesque nature of the canal space as well as importance of wildlife habitats. It is important to recognise that this informal appearance adds to the value ascribed to it as a parallel world , tranquil and away from road traffic often with the air of a quiet backwater.

The landmarks identified include bridges, areas of open space, and groups of Buildings within the canal corridor. Iit is important that their setting and relationship with the waterways is preserved. Bridges are particularly important landmarks. They help to define the character of each length. Furthermore, bridges can be vantage points and command extensive views along the waterside.

When determining applications for development affecting heritage assets, the council will apply the following principles:

- The presumption will be in favour of the conservation and restoration of heritage assets, and proposals should secure the long term future of heritage assets and seek to reveal their significance, by removing clutter, particularly later additions.

- Proposals which involve substantial harm to, or loss of, any

designated heritage asset will be refused unless it can be

demonstrated that they meet the criteria specified in

paragraph 133 of the National Planning Policy Framework. All

grades of harm, including total destruction, minor physical

harm and harm through change to the setting, can be justified

on the grounds of public benefits that outweigh that harm

taking account of the 'great weight' to be given to

conservation and provided the justification is clear and

convincing (paragraphs 133 and 134).

Public benefits in this sense will most likely be the fulfilment of one or more of the objectives of sustainable development as set out in the NPPF, provided the benefits is for the wider community and not just for private individuals or corporations. It is very important to consider if conflict between the provision of such public benefits and heritage conservation is necessary. - Development affecting designated heritage assets, including alterations and extensions to buildings will only be permitted if the significance of the heritage asset is maintained or enhanced or if there is clear and convincing justification. Where measures to mitigate the effects of climate change are proposed, the benefits in meeting climate change objectives should be balanced against any harm to the significance of the heritage asset and its' setting .

- Applications for development affecting heritage assets (buildings and artefacts of local importance and interest) will be determined having regard to the scale and impact of any harm or loss and the significance of the heritage asset.

- Development should preserve the setting of, make a positive contribution to, or better reveal the significance of the heritage asset. The presence of heritage assets should inform high quality design within its setting.

- Respect for the principles of accessible and inclusive design.

There is a general presumption in favour of the retention of the surviving historic buildings within the conservation area are either listed or considered to make a positive contribution to the character and appearance of the area

The council will require a high standard of design in all alterations and extensions to existing buildings. These should be compatible with the scale and character of existing development, their neighbours and their setting. In most cases, they should be subservient to the original building. Alterations and extensions should be successfully integrated into the architectural design of the existing building. In considering applications for alterations and extensions the council will consider the impact on the existing building and its surroundings and take into account the following:

- Scale, form, height and mass;

- Proportion;

- Vertical and horizontal emphasis;

- Relationship of solid to void;

- Materials;

- Relationship to existing building, spaces between buildings and gardens;

- Good neighbourliness; and

- The principles of accessible and inclusive design.

Changes in use of buildings along the towpath, can lead to external alterations that impact on character of the area. The ground floor walls of industrial buildings tend to have few if any openings in them. Incremental change to these structures could alter the canal's character. Care will therefore need to be taken in balancing the needs of new uses with the character of the historic built form and also the canal setting whilst acknowledging that the overall conservation aim is for the canal to be the defining characteristic of the length. Loose fit buildings may offer scope for reuse within their existing envelopes, but care must be taken to consider the cumulative impact on the conservation area of such alterations. Equally removing some of the twentieth century additions will better reveal the nature of the place. Existing architectural features and detailing which positively contributes to the character and appearance of the conservation area should generally be retained and kept in good repair. Original detailing such as ironwork, timber framed or metal windows set into reveals to express the masonry structure, doors, stone and brick copings to both walls and the canal edge, bridge abutments and parapets add to the visual interest of the canal and its setting. Where these have been removed in the past, replacement with appropriate copies will be encouraged. Opportunities to enhance the appearance of the building through the restoration of missing features or creative adaptions which equal the quality of the original are encouraged.

The choice of materials in new work will be most important and will be the subject of control by the Council. Original materials should be retained and repaired if practical. Generally routine and regular maintenance such as unblocking of gutters and securing rainwater pipes, the repair of damaged pointing, and the painting and repair of wood and metal work will prolong the life of a building or structure, and prevent unnecessary decay and damage. Where replacement is required, materials should be chosen to closely match the original. Generally the use of the original (or as similar as possible) natural materials will be required, and the use of materials such as concrete roof tiles, artificial slate and UPVC windows will not be acceptable. Original stonework and brickwork should not be painted, rendered or clad. This may lead to long term damage to original structural materials, and may be extremely difficult (if not impossible) to reverse once completed.